The small cities and towns booming from remote work

[ad_1]

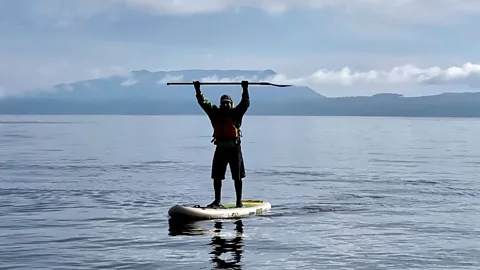

Gonzalo Fuenzalida

Gonzalo FuenzalidaThe new world of remote jobs has small towns and cities exploding with growth as workers explore alternatives to big metropolitan areas. Is this good or bad?

At the tail end of a strict five-month-long lockdown in Santiago, Chile, a sprawling city of about seven million residents, Gonzalo Fuenzalida finally reached his breaking point with urban living. As the owner of Chile Nativo, a travel company that specialises in adventure, he’d always wanted his family to live closer to nature. So, in December 2020, they took a one-month exploratory trip to the woodsy resort town of Pucón, which lies in the shadow of a puffing volcano 780km (485mi) south of the Chilean capital.

Three months later, Fuenzalida rented a house in Pucón near Lake Villarrica, where he and his wife now spend their free time biking, hiking and stand-up paddleboarding. Their seven-year-old son attends school in the neighbouring city of Villarrica, where Fuenzalida rents a two-metre by three-metre office to work.

“In all senses,” he says, “our life has been better.”

Of course, the move has not been without its challenges. The 56-year-old says internet speeds are nowhere near as fast as in Santiago, making it difficult to run his company from his home, which he says “lies in a black hole”. And he hasn’t exactly escaped from traffic, either, which can back up for hours during the area’s peak summer tourism season, especially now that the number of permanent residents has skyrocketed.

Like Fuenzalida, more than 380,000 people migrated away from the Chilean capital during the first year of the pandemic. Most ended up in small towns and secondary cities like Pucón, with more space and greater natural amenities. It’s a phenomenon that has played out around the world, as workers shun major metropolitan areas – and their high costs of living – for less expensive rural areas that are more conducive to their lifestyles.

With the pandemic decoupling work and place, it’s now possible to live in areas that haven’t historically offered jobs for certain professionals. For some secondary cities and smaller towns, this presents an opportunity to reverse brain drain, counter aging populations and inject money into city coffers.

But for others, this new trend has distorted housing markets, priced-out working-class residents and brought big city problems to small cities that were wholly unprepared for them.

Getty

GettyThe latter scenario has been particularly prevalent in America’s Intermountain West, which is home to the three states with the highest growth percentages between 2020 and 2021: Idaho, Utah and Montana. Oxford Economics recently named Boise, Idaho, the most unaffordable city for US homeowners, thanks to an influx of new remote workers from high-cost coastal cities such as Seattle and San Francisco. The median home price in this city of 235,000 is now $534,950 (£395,000) – 10 times higher than the median income.

Big-city problems like gentrification, homelessness and air pollution are all on the rise, adds Rumore, while the overheated housing market (exacerbated by short-term rentals) has made it difficult for businesses in the service industry to maintain staff, since employees can’t afford rent. Rumore notes that Salt Lake City, which has a population of about 200,000, is emblematic of other urban centres in the Intermountain West, which are known for having ample natural amenities, good recreation opportunities, access to open space and a high quality of life.

“With the shift that’s been going on over the last year, we are seeing wealth move into these communities,” she says, noting that many new residents still earn their income in a high-earning area but now live in a lower-earning area. “That’s a major transition that happened overnight that really takes years and years for markets and communities to adjust to.”

Rumore believes this transition can play out in one of two ways. In the more idealistic scenario, the new arrivals plug into the community, while their wealth and resources lift everyone up. In the scenario she worries may be more common, however, the new arrivals extract from the community, they drive up prices and their purchasing power overwhelms those whose jobs are tied to local companies.

This trend of migration out of major cities has been somewhat contentious in the US, but it’s taken a different tone across the Atlantic. With a median age of 42, Europe is the oldest continent in the world. For decades, low birth rates and mass migrations to urban centres such as London, Paris and Madrid have left small towns and secondary cities shrinking. For many of them, the pandemic offers a glimmer of hope.

Getty

Getty“There is an unprecedented chance in Europe to save many rural areas,” says Marcus Andersson, CEO of Future Place Leadership, a Stockholm-based consultancy that studied the implications of remote work and new relocation patterns. “Many of them are on the brink of bankruptcy – they can’t survive as functioning places or functioning administrations – and this is a really great opportunity … because they are now attracting the very people they need to attract: those that have kids or are on the way of starting a family.”

Ireland, where the rural-urban divide dominates politics, has seized the moment like nowhere else in Europe. It made a major push last March to decentralise away from Dublin with a new rural development policy that Rural and Community Development Minister Heather Humphreys said was “the most ambitious and transformational policy for rural Ireland in decades”.

The plan includes €2.7 billion (£2.3bn, $3.1bn) to roll out superfast broadband across the nation. The idea is to turn dying pubs into working hubs, giving declining villages a new lease on life. The initiative also offers millions of euros in financial support for regional authorities to turn vacant properties into a network of more than 400 remote working facilities as well as tax breaks for individuals and companies that support homeworking.

Of course, the question in Japan and around the world remains the same: will those who relocate to small towns and secondary cities stay once the pandemic subsides?

Gonzalo Fuenzalida

Gonzalo FuenzalidaAndersson thinks creating the right ecosystem will be key to capitalising on this opportunity since remote workers don’t just work from home; they work in coffee shops, cafes, co-working spaces and community centres.

“What these places need to do is to create meeting spaces for people and networks where they can interact, learn from each other and grow together,” he says. “They need to become a little bit of what the big cities used to be for people, for companies and for innovation.”

In general, Andersson believes those who have moved away from major metropolitan areas will stay in their new homes, but they may also maintain a link to the place from which they came, such as a smaller flat or co-living place. “We’re coming from a situation where it was either-or,” he explains. “Now, you can be in both places.”

Rumore says that, in the US, she’s seen anecdotal evidence that some big-city workers who relocated to small resort towns last year are now on the move once again. Yet, they aren’t necessarily going back home. “When you realise you don’t want to live in small town Utah, but Salt Lake’s got really good outdoor access, too, you think, ‘I should just move there instead of Seattle or Silicon Valley’,” she explains, noting that this may put even more strain on cities in the Intermountain West.

As for Fuenzalida in Chile, he has no plans of giving up his new life in the resort town of Pucón anytime soon. He’s tapped into a strong community of outdoor enthusiasts, found work-arounds for his internet issues and purchased a plot of land in the forest to build a new home and office. “For a family like ours that is really connected with nature,” he says, “this is exactly the life we wanted.”

[ad_2]

Source link