Norway’s far-flung isle with a Viking spirit

[ad_1]

Anisha Shah

Anisha ShahViking heritage is imprinted into Norway’s 1,700 wild and westernmost isles that lie at the opening of the North Sea – where one islander has devoted his life to preserving the past.

Anisha Shah

Anisha ShahOur islands have fish, oil and resources, but traditional seafaring values were also made here. We must preserve this heritage for country and future,” said Gunn Åmdal Mongstad, Solund’s mayor.

Anisha Shah

Anisha ShahIn Norway’s westernmost region, daylight never seems to break though the dense cloak of winter sky. Each day, there’s only a few hours to marvel at the watery archipelago of Solund that rises from the sea like a phantasm of more than 1,700 desolate islands, islets and crags, all flung off the country’s coast. Only around 20 of these isles are inhabited.

Isolation is ingrained in the identity here. The Sulingen (a nickname for Solund locals) are historically a self-sufficient and resilient seafaring people, many of whom can trace their ancestry back to the Viking Age. Cut-off from Norway’s mainland until 1960 when a road was built to the village of Hardbakke, Solund’s administrative and economic centre, on the island of Ytre Sula, the sea has been their source of survival for centuries.

“The sea is the sole thoroughfare,” said Kjell Mongstad, Solund’s finance minister. “It gives and takes. It always has. We’ve adapted our lives to its rhythm.”

Anisha Shah

Anisha ShahLocated at the opening of the North Sea, the island municipality adorns the mouth of Sognefjord, the longest and deepest fjord in the country. Due to their remoteness, many of these windswept and wild islands can only be accessed by a postal boat that departs from Hardbakke.

While the family-run boat service is invaluable for delivering essentials such as medicine, groceries and news (mobile signal is intermittent here), it also offers islanders a chance for human connection when the skipper, Hans Gåsvær, or his brother-in-law, Tom Færøy, jump on shore to chat.

Its two boats – Stjernesund, which accommodates up to 28 people, and Sulejet, carrying up to 16 – also offer twice-daily passenger service for locals year-round, as well as a scenic and novel way for tourists to explore the islands during the summer months. As a fellow islander, Gåsvær is flexible with timings and allows passengers to call in advance to book their spot for 55 kroner (about £5).

Anisha Shah

Anisha ShahFor Roar Moe, the postal boat is a lifeline. For more than 20 years, he has lived alone on Litle Færøy island in a timber house that he built himself, with just wild sheep and sea otters for regular company. With no noisy neighbours and no pollution, he describes his life as idyllic and simple, but anything but solitary.

“Although I am alone, I am not lonely,” he said. “People come to visit me and to help me, and I really appreciate that. It makes me feel I am in a connection with nature, the elements and the community around me.”

Anisha Shah

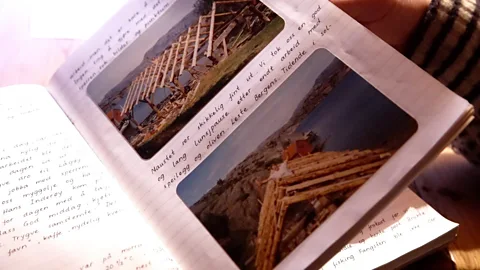

Anisha ShahMoe discovered wild and uninhabited Litle Færøy in 1991 (though he didn’t move there for another 10 years). He’d been scouring Solund for suitable locations for his passion project of recording and archiving Norway’s seafaring and boat-building traditions, through texts and photographs, before they vanish. Today, these traditions have been sidestepped by modern technology and methods: fibreglass replaces wood, and digital navigation supplants sails and steering.

Not only would Litle Færøy offer him the perfect place to build a boatyard, but it would allow him to host summer camps for teaching traditional skills to young people, helping to preserve the Viking heritage of coastal Norway. He also planned to restore Viking-era boats using traditional techniques and materials, and craft replicas for educational purposes.

Anisha Shah

Anisha ShahWe call this project here, ‘to fill new wine into old bottles’. And that means to teach young people to pool traditional ancestral skills with modern technology,” Moe said.

Anisha Shah

Anisha ShahThe Vikings gained their seafaring knowledge and built their legacy through practical experience – such as by intuitive navigation and an understanding of the natural environment – and passed it down from one generation to the next. Similarly, Moe’s grandfather taught him seamanship the old-fashioned way, which has seen him through some hair-raising moments at sea.

“Today, we have machines to build boats but if they break down at sea, I want young people to know how to fix with their hands and think with their heads,” he said.

Through his summer camps, Moe encourages young people to think for themselves, create solutions when problems arise, and in turn gain confidence. That’s the legacy he dreams of leaving, one that was almost lost in the archipelago just a few decades ago.

Anisha Shah

Anisha ShahAfter the discovery of oil in the North Sea in the late 1960s, the country saw significant economic growth. But while the mainland started to boom – investing in airlines, railroads, steel mills and power plants – remote Solund saw little benefit and was largely forgotten.

The archipelago remained dependent on its fishing traditions, and many islanders fled to large cities for better job prospects. According to Kjell Mongstad, Solund’s population plunged from about 2,000 inhabitants in the 19th Century to just 814 by 2018. New opportunities on the mainland, combined with new maritime technologies, quickly relegated traditional boats to museums and banished coastal Norway’s ancestral seafaring legacy to rose-tinted memories.

“Along coastal Norway, people bought modern, fast boats – in their boathouses, they had old boats, old equipment, old fishing gear, and, I’m sorry to say, they burned it all,” Moe said. “The skills and how to run a lifestyle close to the elements disappeared.” This struck a chord with Moe, and is why he has dedicated his life to preserving the past.

Anisha Shah

Anisha ShahIn addition to Moe’s maritime restoration project, other efforts to care for the archipelago have sprouted in recent years. After travelling to and seeing other places, Solund’s inhabitants realised that they were living amid unparalleled, pristine landscapes and began to conserve the coastline through forestry management, cleaner fishing techniques and the use of sheep to control the local heather.

They were soon rewarded when the region was designated as one of 15 natural heritage sites in Norway by the government’s environmental department in 2009. In 2017, Solund was named Sognefjord Coastal Park for its protection of the natural landscape, and was one of eight regional parks recognised by the Norwegian government. And through Norske Parker (Norwegian Parks), it has raised enough funds to apply for Unesco Global Geopark status this March, Kjell Mongstad said.

Anisha Shah

Anisha ShahThese designations have boosted visitor numbers as travellers come to seek out authentic experiences in this peaceful pocket of the country.

Many come for outdoor adventures during the temperate months, which span from April to October. Often described as the ‘Venice of Norway’, the fjord coast is a paddler’s paradise, while hikers are rewarded with waymarked paths, views over the mountainous islands and tiny communities to explore.

Winter, however, brings a heightened romanticism, with dark days and tempestuous nights, while cosy cabins make for perfect refuges from the mighty forces of nature.

Anisha Shah

Anisha ShahAlthough a gentle rise in tourism is welcomed, as reasonable numbers help retain the pristine environment without overwhelming the tiny local population, there’s also a need to attract more permanent settlers to Solund. For the government to continue funding essential services, such as the postal boat, there needs to be a significant local population. Solund’s mayor, Gunn Åmdal Mongstad, says she is very conscious of the need for more young people to settle here and raise families, and not just leave an ageing population behind.

Luckily for Solund, its favourable work-life balance and proximity to nature is attracting more people. According to Gunn Åmdal Mongstad, Solund is home to people of 20 nationalities, with more and more young people returning or relocating, bringing with them a wealth of new skills and creativity. In the local church, for example, Russian resident Lucy Savchenko expertly plays piano, offering musical entertainment at community events. Also, a band of young men, Magnus Vangsnes Bjørgo, Thomas Frøyen and Bjarne Iestra, have recently moved to the region with their wives and families from other Scandinavian countries.

They all cite the islands’ outdoor lifestyle and its strong sense of community as a huge draw.

Anisha Shah

Anisha ShahMoe says that it takes a village to thrive here. Living alone on his island would not be possible without the help of his friends and fellow Solund residents, who check in with each other, especially during times of turmoil.

And since moving to Solund, he’s found more ways to be part of the larger community. He’s on the board of the local history association, Solund Sogelag, and has begun lecturing annually in the US, presenting his knowledge of coastal Norway’s heritage and culture at Norwegian Friends of America, an organisation that promotes kinship between the two nations.

It seems locals like Moe are helping this once-forgotten archipelago find its stride again and are enticing the rest of the world with its nature and island lifestyle. It’s a place that dances to its own rhythm where the waves, winds and wilderness will continue to dominate, just as they always have.

To the Ends of the Earth is a multimedia series from BBC Travel venturing to some of the most remote corners of the planet and unveiling what it’s like to live there.

[ad_2]

Source link