The 30-year-old soundtrack to hedonism

[ad_1]

Features correspondent

Dave Swindells

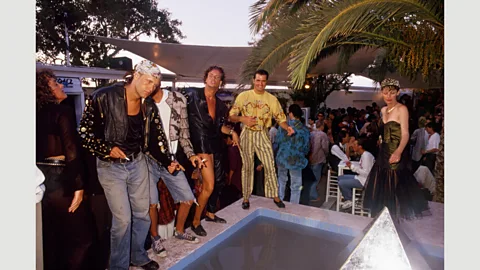

Dave SwindellsIn the summer of 1988 – labelled ‘the Second Summer of Love’ – acid house went from an underground British clubbing scene to an international phenomenon. Thirty years on, Arwa Haider explores how the electronic music took over the world.

Thirty years ago, in the Eastern province of Saudi Arabia, I was hiding in the toilets at my all-girls school, shielding my illicit cassette Walkman from the teachers who confiscated any ‘haram’ music items. I put my headphones on to hear a new track; the electronic beats and bassline surged, a feverish frequency bubbled, and a voice shrieked: “Acieed! Acieed!” I was instantly hooked. The track, taped from a Bahraini radio transmission of the British charts, was We Call It Acieed, by British act D Mob. It was October 1988, and acid-house music had seeped into the Arabian Gulf.

Around that same time in the UK, emotions were high. A heady fever had gripped British nightlife, youth culture and fashion, and acid was the catalyst. Some of the most seminal London clubs (Future, Shoom and Spectrum) were name-dropped in We Call It Acieed; now that acid house was yielding mainstream hits, the ‘serious’ music press were proclaiming that the scene was dead. In fact, although the scene was no longer strictly underground, its independent spirit seemed irrepressible – and its cultural energy was uncontrollable.

“I remember we arrived to play at Spectrum one Monday night, and there was a massive queue around the block,” recalls pioneering British DJ Nancy Noise. “It took a while, but the word had obviously spread. People from different music scenes would come and get inspired.”

Lynn B

Lynn BThe thrill of that era of club culture – and nightlife ever since – has been most vividly captured in the photography and journalism of Dave Swindells, who became the clubs editor of London’s Time Out magazine (and with whom I would later get my first writing job). He recalls hearing acid house music at a soul weekender run by DJ Nicky Holloway in early 1988, and how it initially startled the crowd.

“The first time I heard it, I was like: ‘What the hell is this?’,” laughs Swindells. “The cultural legacy of acid house is that, in the same way as punk, it shocked people, but also opened their ears and eyes to possibilities,” he says. “It blew open the gates. That mad energy was harnessed, and the sense of freedom was one of the most important aspects; people realised that they could run their own parties.”

Dave Swindells

Dave SwindellsThe acid-house scene was a cross-cultural fusion, with the music originally stemming from the black club scene of mid-80s Chicago. Phuture’s Acid Tracks (1987) arguably coined the sound: a raw, impulsive, hypnotic electronic groove, characterised by the pulsing, ‘squelching’ effects of the Roland TB-303 synthesizer-sequencer and the beats of the TR-808 drum machine. The 1982 album Ten Ragas To A Disco Beat by Indian producer Charanjit Singh actually also used this music tech, and sounds incredibly visionary.

The free-spirited ‘love generation’ attitude was born on the Balearic isle of Ibiza and its clubs, notably Amnesia. Nancy Noise had moved to Ibiza in the mid-80s (and brought a playlist back to Britain with her); in the summer of 1987, a group of British DJs including Paul Oakenfold (celebrating his 24th birthday), Danny Rampling, Holloway and Johnny Walker also had a musical awakening together at Amnesia.

Dave Swindells

Dave SwindellsSwindells points out that acid house was British, in the way that people responded to these influences: “In Britain, more than any other place, we have this direct line between the club dancefloors and the pop charts,” he says. “Acid house would really resonate quite rapidly, and people who were not clubbers went nuts for it. A relatively exclusive London club scene was turned into an international phenomenon.”

Acid house reinvented clubbing as a multi-sensory event, which could not be contained within ‘regular’ hours; at Holloway’s 1988 club The Trip, clubbers would spill onto central London’s streets and continue dancing after the venue had shut. At Manchester’s legendary Hacienda, acid house-driven nights like Nude and Hot (which featured a swimming pool on the dancefloor) became world-class destinations. DJ Danny Rampling, who launched Shoom in late 1987, told The Guardian newspaper last year: “We filled the room with apple- and cherry-flavoured smoke and decorated it with painted banners: smiley face logos and slogans. It was a free state of hedonism.”

By late ’88, illegal raves were mushrooming around Britain’s M25 motorway circuit (rave author Sam Williams explained in the BBC documentary A Road To Nowhere: “The meeting point would be one of the service stations… all we wanted to do was dance and party”).

Dave Swindells

Dave SwindellsIn stark contrast, commercial promoters like Tony Colston-Hayter capitalised on the lucrative potential of acid house, throwing massive Sunrise raves. Superstar DJs, branded clubs and the lavish theatrical productions we’d now associate with 21st-Century EDM events have their roots in this rave new world.

The British mainstream press was seriously conflicted by this phenomenon. Tabloids like The Sun ran sensational headlines about heaving dancefloors, drugs (‘acid’ also nodded to psychedelic drugs like LSD and the euphoria-inducing MDMA, aka ecstasy) and police raids, while simultaneously peddling “groovy and cool” acid house T-shirts (“only £5.50 man”). Back in Saudi ’88, I adorned my bedroom wall with the cover of an imported copy of New Musical Express, depicting a policeman tearing up a smiley face; the headline read: ‘Acid Crackdown: Panic In The Streets Of London?’.

Dave Swindells

Dave SwindellsPartying suddenly felt political, in a way that it hadn’t since disco or punk. By the time Britain’s Criminal Justice and Public Order Act 1994 clamped down on illegal raves and ‘repetitive beats’, acid-house sounds were evolving into diverse dance forms including drum’n’bass, club promoters were moving into licensed venues with longer hours, and clubbing definitely felt defined as a ‘culture’.

Acid house brought depictions of clubbing into other art forms, including audio-visual art works such as Jeremy Deller’s 1997 piece Acid Brass, connecting rave anthems and traditional Northern brass bands, and Mark Leckey’s Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore (1999). It became a recurring theme on the big screen, with movies like Clubbed To Death (1997) and Sorted (2000) initially portraying raves as dangerous underworlds, before the US film Groove (2000) captured the celebratory spirit of a San Francisco all-nighter. The acid-house effect is felt in the trippy intensity of Gaspar Noé’s films (particularly 2009’s Enter The Void and his latest, the 2018 dancefloor horror Climax) as well as the melodramatic rush of Mia Hansen-Løve’s DJ-themed youth drama Eden (2014).

Alamy

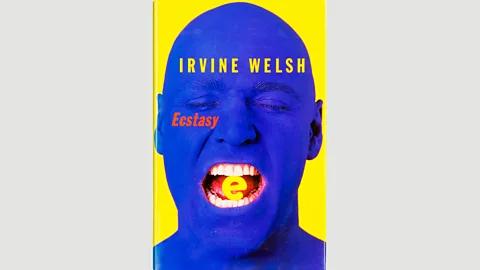

AlamyThe free-spirited creative revolution also influenced modern literature: the works of Irvine Welsh regularly contrast raves with brutal surrealism, and Welsh has also dabbled in DJing. The acid-house scene forms a backdrop in Hanif Kureishi’s The Black Album (1995), while the anti-heroine of Alan Warner’s 1995 novel Morvern Callar runs away to the raves (“The DJ had taken us into the hardest ‘core, and you could see he was letting it run more ambient for a while before he’d start building up the energy again”). Warner, Alex Garland, Nicholas Briscoe and Gavin Hills also contributed acid house-themed short fiction to the 1997 book Disco Biscuits, edited by Sarah Champion.

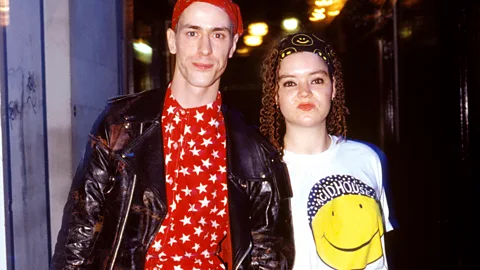

High-street fashion ran with the acid house look, which is now resurfacing for the 21st Century: bright and casual, gender-neutral baggy clothing to counter the heat of the dancefloors. Acid house is where Britain’s underground went pop, and its ideal – that the club should be a place of unity – still resounds at all kinds of nights.

Getty

Getty“Everything was a mish-mash, and everyone looked amazing,” explains Nancy Noise. “We’d swap clothes a lot, because you wanted to give everything away! The atmosphere was free and friendly, even if you didn’t take drugs; it was welcoming – you could be part of something straight away. I think that style of clubbing spread all over the world; people still party like that now – all that togetherness.”

Over the weekend of 15 to 16 September, Nancy Noise is part of a stellar DJ bill for London’s Next Step Forward Festival, celebrating 30 years of acid-house culture. This autumn, Manchester celebrates its clubbing legacy, in the build-up to next year’s International Festival. Acid-house revivals still bring together generations and possibilities. Last December, I went to Shoom’s 30th-anniversary all-nighter in London, and danced alongside veteran Shoomers as well as a youth whose parents had met at the original acid-house parties. There, Dave Swindells introduced me to a jovial 50-something man called Gary Haisman, who happened to have been the voice of We Call It Acieed. I hugged this heroic stranger by the dancefloor, feeling star-struck and smiley.

[ad_2]

Source link