The band that could save music

[ad_1]

Features correspondent

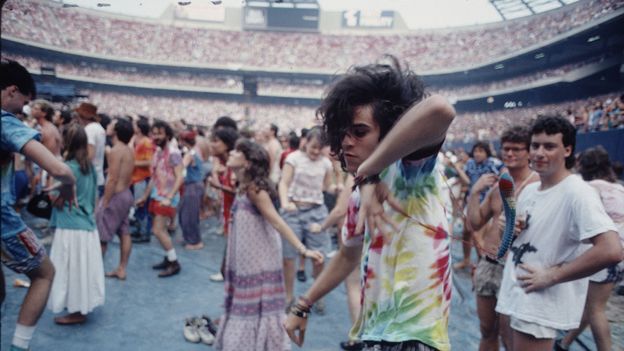

LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images

LIFE Picture Collection/Getty ImagesThe Grateful Dead didn’t rely on their intellectual property alone to build their following. Their relationship with their fans was even more lucrative, writes Greg Kot.

When pundits talk about the musical model for the internet era, they rarely talk about a bunch of prankster-hippies from northern California who helped invent the ‘60s counterculture. But they should.

The Grateful Dead, who are calling it quits after they celebrate their 50th anniversary with three concerts at Soldier Field in Chicago this weekend, were psychedelic pioneers who wrote the soundtrack for the Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test generation. But there’s another equally important aspect to the band’s legacy, though it isn’t discussed and debated nearly as often. The Dead didn’t just define their time but were ahead of it.

Long before Napster debuted and shifted the way music was made, distributed and marketed, the Dead were essentially writing the 21st Century music-business guidebook. In 1994, this future would be defined by technology analyst Esther Dyson as the selling of “services and relationships” through the distribution of free intellectual property.

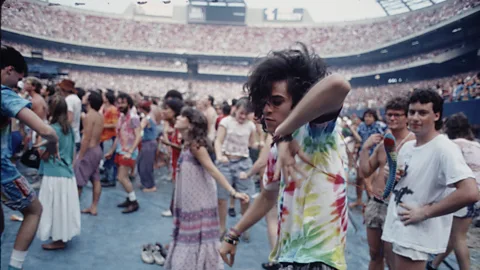

Getty Images

Getty ImagesDyson might’ve had the Dead in mind, because the band had been delivering free services and perfecting relationship building for decades. The band didn’t treat its fans like a marketing demographic, but a community of equals, their co-conspirators on a musical and social adventure.

“If you want to survive in this business,” the band’s late guitarist Jerry Garcia once told me, “you go out there and pick up your audience, you recruit ‘em. That’s who you’re working for.”

The notion of a band ‘giving away’ its music came as a shock to many music industry executives as MP3 files gradually replaced CDs. But the Dead always made it easy for its fans to record its concerts and distribute tapes to their peers around the world. The Dead set aside a ‘tapers section’ near the sound board at its concerts of more than 2,000 people, and became the most widely documented band of the pre-internet era.

The band was worth documenting because none of its shows was a repeat: each was unique in its set list and in the way the songs were interpreted. Unlike digital files, each show was an experience that couldn’t be copied – the relationship was the product. If you missed a show, you weren’t going to see it again. Sure, you could hear it on a tape, but the Dead ethos encouraged and rewarded fans who attended multiple shows, and even began following the band around the country on its tours.

Corbis

CorbisAs for record companies, the band didn’t rely on them much except to distribute its studio recordings. The Dead built its own infrastructure, and became increasingly self-sufficient. Grateful Dead Productions became a hub for concert ticket and merchandise sales, and it morphed into a website that not only sustained the band for the 20 years after Garcia’s death in 1995 but enabled it to flourish.

By going down this route and relying on outside corporations as little as possible, the Dead made the direct-to-fan ideal a hallmark of its operation long before the internet made this a commonplace. The band released many more albums on its own imprint than it did through major labels. Rather than a cheap money grab, these recordings (initiated by the excellent Dick’s Picks series, named after the band’s late archivist Dick Latvala) were often better than some of the band’s studio recordings for the big labels, which increasingly pushed the band to create radio-friendly songs with hired-gun producers.

You want to talk about branding? The Dead didn’t just sell T-shirts, but everything from golf clubs to baby clothes. The band also inspired a raft of books, DVDs and a syndicated radio show, The Grateful Dead Hour. They weren’t just a musical entity, they became synonymous with a lifestyle.

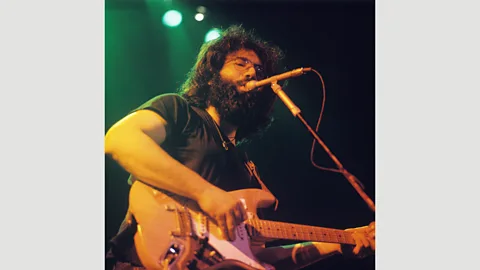

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAnd, despite all those hoary associations with hippies and the free-love generation, the Dead were musical postmodernists in the extreme. The internet helped facilitate cross-cultural blending – not just sampling, but mixing and remixing styles of music that previously didn’t go together. The Dead saw it coming. They stirred up a thick soup of Americana (from blues and bluegrass to jazz, rock and folk) with avant-garde seasoning. It’s not coincidental that one of the first widely recognised mash-ups – a staple of the digital-music era – occurred in 1995, with Plunderphonics sonic pioneer John Oswald’s reshaping of multiple versions of the Dead’s Dark Star.

The lesson was not lost on many contemporary bands and artists, who saw the Dead’s approach not as just a slice of quaint ‘60s nostalgia, but as a way forward. Jeff Tweedy of Wilco, which released its Yankee Hotel Foxtrot album as a free download on its web site as the Napster era dawned, told me soon after that “in some weird way, everything will be like the Grateful Dead. They didn’t need to make records. They were a real band and they were heard, and became part of people’s lives, without making a lot of records. But their music reach everywhere, and now it has a life of its own.”

Greg Kot is the music critic at the Chicago Tribune. His work can be found here.

[ad_2]

Source link