The Black farmer who inspired a US park

[ad_1]

Features correspondent

Constance Mier/Alamy

Constance Mier/AlamyThe son of an enslaved person, Jones went on to become one of the largest landowners in the Florida Keys – and his refusal to sell his land inspired Biscayne National Park.

When the light is just right, there’s no horizon line in Biscayne National Park. Blues from the sky melt fluidly into clear-green waters, where scattered tangles of mangroves shelter young sharks and great herons.

These several dozen northernmost islands of the Florida Keys archipelago are best known for their quiet sunsets and offshore coral reefs, but in 1961 it seemed inevitable they would become south Florida’s next luxury waterfront community. Developers had even ferried a voting box and 14 absentee landowners to one of the sparsely populated islands, where they cast ballots making their new city of Islandia official.

“There were plans for high-rise buildings, an airport, amusement parks and the whole nine yards,” said Gary Bremen, a former park ranger who worked at Biscayne for nearly 30 years. “It was the last developable undeveloped waterfront in Dade County.” During that time, a company called Seadade, was also staking its claim to the bay with an 18,000-acre oil refinery that would carve a 15-mile channel through the ecologically fragile shallows.

Christy Thibodeau/NPS

Christy Thibodeau/NPSThere was just one wrench in these development plans: a 6ft 4in Black farmer-turned-fishing guide named Sir Lancelot Garfield Jones. Lancelot and his brother, King Arthur, owned three islands in the bay, likely making them the largest landowners in the area. Though they hadn’t been invited to the Islandia vote, Seadade was courting them with a multi-million-dollar buyout. But Lancelot didn’t like the idea of mass development, and he knew neither project could proceed without his cooperation.

“He refused. He just said, ‘No, I’m not going to do that’,” said Dr John Nordt, a friend of Lancelot, who passed away in 1997, aged 99. “That spurred on a movement that was put together by several congressmen to preserve Biscayne Bay and create a national monument, which eventually became Biscayne National Park.”

Lancelot was born on a sailboat in Biscayne Bay in 1898 and would live on the island of Porgy Key for the next 94 years. His father, Israel “Parson” Jones, was likely born enslaved, and his mother, Mozelle, was a Bahamian immigrant. They started their family homestead in 1897 by buying the 63-acre island for $300.

“He bought it for a ridiculously low amount because it was seen as basically next to worthless,” said Joshua Marano, maritime archaeologist at Biscayne National Park, who explained that Porgy Key had been inundated with salt from a recent hurricane when the family purchased it. “But he was able to go out there and try some different planting techniques that became very successful.”

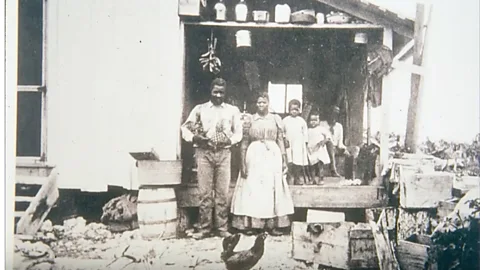

John Nordt

John NordtThanks to Parson’s tireless work ethic, the Jones family went from being the first Black landowners in the Keys to the largest key lime farmers in the state. They bought two other islands, installed a mini-railroad to haul fruit and dug a 300ft trench through solid limestone so boats could reach the shore to load cargo. By 1912, Parson had hand-built a two-storey, six-bedroom house.

While the Jones’ business was successful, Porgy Key was an isolated place to grow up. It’s located six miles offshore, and when Parson built the family homestead, there were fewer than 5,000 people in Dade County (which extends from Miami south to the Everglades). The brothers kept themselves entertained by fishing and exploring, and Lancelot became deeply inspired by the natural world.

By the mid-1930s, the success of the family business began to wane. Mozelle and Parson had died and a series of hurricanes damaged crop production. Prohibition had initially caused the bottom to fall out of the lime market, and the introduction of imported Persian limes further reduced demand. The brothers started supplementing their income by working as fishing guides at the exclusive Cocolobo Club on nearby Adams Key.

“The people hanging out there, they were Firestone, Seiberling, Florsheim and Maytag – names that are products more than they are people,” said Bremen, referring to the famed US tyre, shoe and appliance inventors. “[US celebrities like] Will Rogers, Johnny Weissmuller, Irving Berlin. Here’s all these really wealthy, rich white guys and here’s this couple of brothers who are scraping out a living doing whatever they can to keep surviving.”

John Nordt

John NordtIt wasn’t enough to keep Arthur around, however. He signed up for World War Two, leaving Lancelot alone on Porgy Key, which is how it would remain for the next 50 years. Of this, Lancelot once told reporters: “I am alone, but I am not lonely. When you have plenty of interests like the water and the woods, the birds and the fish, you don’t get lonely.”

Lancelot continued to guide throughout those decades, entertaining more celebrities, businessmen and presidents at the Club, including US president Richard Nixon.

“He was actually sought after,” said Bremen. “He would talk about hanging out with President Hoover or President Johnson and essentially baiting them with questions about [legislation] that was coming up, just to see what they would say. That’s pretty extraordinary for anybody, but especially for someone that looked like him when everyone else who looked like him was riding in the back of the bus and drinking from separate water fountains in Miami.”

While the Jones’ were somewhat isolated from the turmoil of the Jim Crow south, the area around Biscayne Bay was in the heart of it. The town of Homestead, at the entrance of today’s park, was a Ku Klux Klan stronghold and the site of several lynchings. The visitor centre is also built atop a former African American segregated beach. Predictably, the “Colored” beach was hotter, buggier and had fewer amenities, but those who used it remember it as a place of happiness, according to Iyshia Lowman, who researched and gathered oral histories about the park.

Sandra Foyt/Alamy

Sandra Foyt/Alamy“They had a dance hall, church events, birthday parties. There were families building memories there. It should be remembered that way,” Lowman said. “We can focus on that and still understand that we have some growing to do, and there’s nothing wrong with that.”

The beach ceased being used following the Civil Rights Act of 1964. By then the movement to protect Biscayne Bay was also underway, facilitated by a small environmental activist group inspired by Lancelot’s refusal to sell his land. Arthur died in 1966, and two years later, Lancelot’s old angling companion, President Lyndon B Johnson, officially signed the bill creating Biscayne National Monument (which would become Biscayne National Park in 1980). In 1970, Lancelot became the first and largest private landowner to sell land to the government. The price: $1.27m for his 277 acres, which many estimated to be fraction of what he could have earned by selling it to the oil company.

“The idea that a man who had once been enslaved saved enough money to buy his own land, then eventually had a son who could have sold that land to developers, but made a choice instead to sell it to the Park Service for a lot less because he believed that it would be available to people, I mean, that’s an incredible story of a Black person in America thinking about land and place in a very specific way that you don’t hear often,” said author and cultural geographer Dr Carolyn Finney, who researched the Jones story for the National Park Service. “It doesn’t mean it doesn’t happen often. You just don’t hear it often. And that, for me, is what’s so powerful about the story.”

Lancelot put a condition in the sale that he be able to continue to live out his days on Porgy Key, and began educating school children about local ecology, especially fish and underwater sponges.

John Nordt

John NordtIn 1992, Lancelot finally left his home on Porgy Key. The day before Hurricane Andrew made landfall, park rangers were able to convince the 94-year-old to evacuate, which ended up being a wise move. The category five storm destroyed every structure on the island. Lancelot never moved back, instead living out the rest of his life on the mainland. When he died in 1997, the population of Miami-Dade County had exploded to nearly two million people, but Porgy Key and the rest of the Biscayne wilderness remained preserved.

“I think the most important part of Lance’s story is having an appreciation for where you live and what you have, and the understanding of how nature works,” said Nordt. “It’s not about building houses. It’s not about oil refineries. It’s not necessarily about big boats. It’s about enjoying where you are, the sunshine, the birds, and how the water flows in and out like liquid light. It’s pure. And he enjoyed life.”

Since Lancelot’s passing, more efforts have been made to tell the lesser-known stories of Biscayne. In 1827, the Spanish slave ship Guerrero sank south of Porgy Key with 561 captive Africans on board. Intrigued by the Jones’ family legacy, archaeologist Brenda Lanzendorf and youth advocate Ken Stewart established Diving With a Purpose, a nonprofit group of mostly Black scuba divers, and began training members in underwater archaeology so they could help find and document the wreck.

In 2015, the seven-mile entrance to the park was renamed Sir Lancelot Jones Way, thanks in part to the efforts of the outdoor and environmental mentorship programme The Mahogany Youth, which works to connect mainly Black children with nature. The second Monday of October has even been declared Sir Lancelot Jones Day in Florida. Currently there are eco-kayak tours around Jones Lagoon, a scenic shallow-water lagoon likely named after the Jones family, and the park is working on ways to open up what’s left of the Jones homesite to visitors.

Sipa US/Alamy

Sipa US/AlamyAs Marano said: “The Park Service is a safe place to tell both difficult and inspiring stories, especially in today’s environment, and help in the process of understanding and healing within the greater community. We want to do that as much as we can.”

Rediscovering America is a BBC Travel series that tells the inspiring stories of forgotten, overlooked or misunderstood aspects of the US, flipping the script on familiar history, cultures and communities.

[ad_2]

Source link